Money Laundering & Murder in Colombia: Official Documents Point to DEA Complicity

Kent Memo’s Corruption Allegations Bolstered by FOIA Records, Leaked U.S. Embassy Teletype

By Bill Conroy

Special to The Narco News Bulletin

May 18, 2008

The bullet-riddled body of a DEA informant was dumped on the street in front of his home in Bogotá, Colombia, in June 2002. The informant, who had a background as a self-taught chemist, had been released from a Colombian prison in March of that year, after being arrested by Colombian police on narco-trafficking-related charges.

Prior to his lifeless body being thrown from a car onto the hard pavement of a Bogotá road, the informant had been reported missing after embarking on a trip to the airport.

The informant’s death was due to a deceit that has since metastasized inside the DEA and is spreading like a cancer, threatening to undermine any credibility the agency might have gained in the years since its creation in the 1970s.

The core of that deceit is outlined in a memo leaked to Narco News in 2006. That memo, drafted by Department of Justice attorney Thomas M. Kent in December 2004, contains some of the most serious allegations ever raised against U.S. antinarcotics officers: that DEA agents on the front lines of the drug war in Colombia are on drug traffickers’ payrolls, complicit in the murders of informants, and directly involved in helping Colombia’s infamous paramilitary death squads to launder drug money.

To date, officials with DEA — and the Department of Justice under which it is housed — have been content to dismiss Kent’s allegations as being without merit, the product of a simple turf war between rival agents. (For more on the Kent memo, see Narco News’ Bogotá Connection series at this link.)

However, Narco News recently obtained documents through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request as well as additional information from DEA sources that lend credence to the Kent memo and provide new insight into a few of the specific corruption allegations outlined in that memo.

The FOIA documents obtained by Narco News appear to implicate a former high-level Bogotá DEA agent in a perjury that led to the death of the DEA informant. That agent has since been promoted to command a major DEA field division in the United States.

In addition, the new information provided by DEA sources appears to implicate another former high-level Bogotá DEA agent (who went on to oversee a major inter-agency antinarcotics task-force program) in money laundering activities linked to a Colombian rightwing paramilitary group.

Death of an Informant

The FOIA documents provide background on a narco-trafficking case that was handled by a DEA group supervisor in Florida named Edward Fields. The documents were obtained from the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), which hears cases related to whistleblowing by federal agents.

Fields authored a memo in June 2001 (under orders from his superiors) that outlined a “factual chronology of events” leading up to the arrest of several DEA informants in Bogotá. Those informants were assisting Fields in a case revolving around a Colombian narco-trafficking ring’s use of chemistry to conceal cocaine and heroin that was being smuggled into the United States and Europe.

Fields MSPB case was sparked, in part, by the retaliation he suffered in the wake of writing the memo. The administrative judge in the case ultimately dismissed Fields’ case, claiming the MSPB had no jurisdiction because the memo drafted by Fields did not constitute an act of whistleblowing.

But the court of public opinion does have jurisdiction over Fields’ pleadings, and based on a reading of those pleadings obtained through the FOIA request, they do seem to mirror nearly precisely the allegations advanced in the Kent memo.

Following is a summary of the account of the acrylic case provided in the Kent memo.

“Specifically, the narcotics traffickers in Colombia were infusing acrylic with cocaine and shaping it into any number of commercial goods,” the Kent memo states. “The acrylic was then shipped to the United States and Europe where, during processing, the cocaine was extracted from the acrylic.”

Informants working for Group Supervisor Fields’ Florida agents sent samples of the cocaine-laced acrylic to the DEA, but the agency’s chemists couldn’t figure out how to extract the cocaine. As a result, the Florida agents decided to have the informants come to the United States with a sample of the acrylic, so they could walk DEA’s chemists through the extraction process.

“Agents contacted the Bogotá Country Office to discuss the informants’ planned travel and their bringing cocaine out of Colombia infused in acrylic,” the Kent memo states. “They were advised that the best tact was for the informants to carry it out themselves.”

But when the informants got to the airport to leave for the U.S., they were arrested. A DEA agent in Bogotá, it turns out, had told Colombian officials to “lock them (the informants) up and throw away the key,” according to the Kent memo. The Bogotá agent then claimed that he had no idea the Florida agents had given the informants permission to transport the cocaine.

“His misrepresentations were backed by another agent in Bogotá,” Kent states in the memo. “The informants were imprisoned for nine months while the accusations flew back and forth. Once it was determined that the agents in Bogotá were lying, the informants were released. One of the informants was kidnapped and murdered in Bogotá where he had gone into hiding.”

Following is the account of the acrylic case contained in Fields’ MSPB pleadings:

The acrylic containing the narcotics could be molded into any form and any color. The [Colombian narco-trafficking] organization was said to be producing acrylic containing narcotics in the form of key chains, lamps, picture frames and shower doors. The organization was planning to ship approximately three to four tons annually, with each shipment being approximately 400 kilograms. The destination for the cocaine shipments was Europe, while the heroin shipments were destined for the United States. The sources [informants] alleged that the cocaine yielded approximately 90 percent return when converted back to cocaine base. The above information was communicated by the KLRO [DEA’s Key Largo, Fla., Resident Office] to DEA Bogotá, along with the names and location of the factory producing the acrylic. …In February 2001, plans were made to have two Cooperating Sources [the informants] travel to Miami with a sample of the acrylic. The purpose of this trip was to have one of the Cooperating Sources demonstrate the extraction process. This particular source was a self-taught chemist. Arrangements were made to have the sample analyzed at the Florida International University Chemistry Department with DEA and USCS [U.S. Customs Service] chemists present. In June 2001, DEA Bogotá issued the self-taught chemist source a Significant Public Benefit Parole Visa, for travel to Miami, based on a DEA Miami request.

Javier Pena, special agent in charge of DEA’s San Francisco field division. DEA website |

Fields was caught by surprise by Pena’s claim, as is reflected in his pleadings before the MSPB obtained through Narco News’ FOIA request:

At some point after the arrests of these Confidential Sources [the informants] in Colombia, the DEA Office in Bogotá claimed that it was unaware that the Confidential Sources would be traveling from Colombia to the United States with a sample of the acrylic substance containing cocaine. In his June 25, 2001 memorandum, however, GS Fields recounted a telephone conversation that he had with Bogotá DEA [agent Javier Pena] ….On or about June 8, 2001 [prior to the informants’ arrest in Bogotá], … Fields telephonically contacted [Pena] to inquire as to how the country clearance request [for the Bogotá informants] should be addressed, reference to bringing the acrylic product to Miami for testing. I [Fields] advised [Pena] that the product was purported to be a mixture of acrylic and cocaine. …

After Pena denied any knowledge of Fields’ acrylic-busting operation, the informants soon found themselves in prison in Bogotá, where they stayed for some nine months while Fields worked with Colombian prosecutors to secure their release. In the mean time, however, their identities as DEA informants were compromised, DEA sources say, leading to the subsequent murder of the informant who was the “self-taught” chemist.

Justice Department attorneys defending the government against Fields’ MSPB litigation contend that his June 2001 memo outlining the events that led up to the informants’ arrest in the acrylic case “does not allege … any wrongdoing.”

“It is simply a chronology or a time line of events related to the investigation,” the government’s pleadings argue.

Fields attorney, however, takes a sharply different view of that memo:

[DEA Group Supervisor Edward] Fields, at the time he drafted the June 25, 2001, memorandum [about the events leading up to the arrest of the informants], knew full well that the DEA Bogotá’s false denials in this regard [concerning the acrylic case] would violate, at the very least, DEA’s Standards of Conduct relating to false statements and falsification, as well as potential criminal statutes relating to perjury, obstruction of justice and making false statements to federal law enforcement officials.

(Click on this link to see a sample of the FOIA documents.)

Pena, who now serves as the special agent in charge of DEA’s San Francisco field division, which oversees northern California, declined to talk with Narco News about his role in the acrylic case. Casey McEnry, press spokesperson for DEA’s San Francisco office, referred Narco News to DEA Headquarters for comment.

Michael Sanders, a spokesperson for DEA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., declined to comment as well, other than to say: “This would be an internal investigative matter, if it came to that, and those stay under lock and key.”

This is not the first time that Pena’s name has come up in relation to corruption allegations, however.

In the late 1990s, Luis Hernando Gómez Bustamante, one of the leaders of Colombia’s North Valley Cartel narco-trafficking syndicate, became a target of a Drug Enforcement Administration investigation called Operation Cali-Man, which was overseen by a DEA supervisor in Miami named David Tinsley.

In mid-January 2000, Gómez Bustamante attended a meeting in Panama to discuss possible cooperation with the DEA. According to one of Tinsley’s informants, during the course of that meeting Gómez Bustamante revealed that a high-level DEA agent in Bogotá was on the “payroll” of a corrupt Colombian National Police colonel named Danilo Gonzalez — who was eventually indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice on narco-trafficking charges. (In the spring of 2004, Gonzalez, while preparing to surrender to U.S. authorities, was assassinated at his lawyer’s office in Bogotá.)

The informant, an individual named Ramon Suarez, later told DEA internal affairs investigators that the U.S. federal agent identified by Gómez Bustamante as being on the “payroll” was Javier Pena, who at the time was the assistant country attaché at the DEA office in Bogotá.

When questioned by DEA internal affairs investigators in 2002, Pena denied the charge. However, he did concede he had a relationship with Colonel Gonzalez dating back to the early 1990s, when Colombian and U.S. law enforcers worked together to hunt down the notorious narco-outlaw Pablo Escobar.

(Those allegations against Pena can be found in a DEA report obtained previously by Narco News and available at this link.)

Drug Money

Pena is not the only former Bogotá DEA agent who is in the sights of the Kent memo, DEA sources point out.

Pena’s boss at the time he was stationed in Bogotá, the DEA sources contend, also appears to be implicated in alleged corruption linked to the AUC — an infamous rightwing paramilitary group in Colombia.

From the Kent memo:

One of the corrupt agents from Bogotá … was recently intercepted over a wiretap. That conversation links him to ongoing criminal activity. Specifically, in it he discusses his involvement in laundering money for the AUC. That call has been documented by the DEA and that agent is now in charge of numerous narcotics and money laundering investigations.

The United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, or AUC, (now supposedly disbanded) is widely recognized as a major player in narco-trafficking and arms dealing. Working closely with various sectors of the Colombian military, it has fielded death squads responsible for murdering thousands of Colombians.

Kent’s allegation concerning the Bogotá DEA agent’s links to the AUC is supported by information recently provided to Narco News by DEA sources. That information, a redacted version of a confidential U.S. Embassy teletype message, summarizes a series of wiretapped conversations that reference a former high-level Bogotá DEA agent named Leo Arreguin Jr.

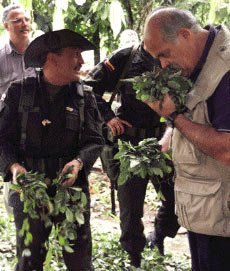

Leo Arreguin inspecting coca crops during his time as chief of the DEA’s Bogotá office. Photo: Hoy Online (Ecuador) |

The teletype originated in the U.S. Embassy in Bogotá and was sent on Dec. 14, 2004, to five other U.S. Embassies in Latin America and Europe as well as to half a dozen DEA offices in the United States — including DEA Headquarters.

The teletype is titled “Update of recent Colombian telephonic intercepts obtained in October and November 2004” and it references the following case number: ZE-03-0053.

The teletype indicates that the intercepted conversations involve numerous calls to Belgium made by an individual named Fernando Pelaez-Arango, who is identified as one of the “targets” of a joint DEA and Colombian National Police narco-trafficking investigation involving members of the “the Colombian AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia) narco-terrorist group.”

Pelaez-Arango, the teletype alleges, is “a major money launderer for members of this drug organization.”

“Pelaez-Arango has been currently coordinating with an individual in Belgium identified only as … Mr. Jhon, in order for Mr. Jhon to send Pelaez-Arango approximately one (1) million U.S. dollars to Pelaez-Arango’s bank account(s) in Colombia,” the U.S. Embassy teletype states.

Following, from the U.S. Embassy teletype (link here), is a summary of several intercepted calls involving Pelaez-Arango and Mr. Jhon in Belgium. DEA sources tell Narco News that the conversations are about a money laundering transaction — though the discussions are carried out in coded language.

Recorded conversation No. 11Pelaez-Arango talks to unkown male #1 about someone named Arreguin who called unknown male #1 and passed to him the message that Mr. Jhon in Belgium left the following phone number for Pelaez-Arango to contact Mr. Jhon at. … There was also an additional SAT [satellite] phone number that was left for Pelaez-Arango to contact as well, which was for someone named Sonia. … During the conversation with unknown male #2, Pelaez-Arango tells unknown male #2 that Arreguin called Pelaez-Arango and told Pelaez-Arango that he (Arreguin) was going to try to fix the problem in the United States. [Emphasis added.]

Recorded conversation No. 13

Pelaez-Arango calls Mr. Jhon and they greet each other. Mr. Jhon tells Pelaez-Arango that Mr. Jhon has been expecting a call from Pelaez-Arango. Mr. Jhon says that he was with the lawyer and the lawyer asked Mr. Jhon how much money Pelaez-Arango wants, either nine (9) million or one (1) million USD [U.S. dollars]. Pelaez-Arango says that he can use one (1) million USD. Mr. Jhon says that he is going to call the lawyer now, and then call Pelaez-Arango back in a few minutes.

Recorded conversation No. 14

Pelaez-Arango calls Mr. Jhon back and they greet each other. Mr. Jhon tells him that what Pelaez-Arango has to do now for Mr. Jhon to get the money out is as follows. Mr. Jhon tells Pelaez-Arango that Pelaez-Arango has to call this number that Mr. Jhon is going to give him. ... The lawyer’s going to include all the relevant documents (security documents), so that they (Mr. Jhon) can get the money out of the bank and send it to Pelaez-Arango, and that the lawyer is going to charge $10,000.00 USD for everything (lawyer fees). … Mr. Jhon says that he talked to the lawyer today. Mr. Jhon tells Pelaez-Arango to call the lawyer today and then call Mr. Jhon back. Mr. Jhon stresses that this must be done urgently.

Given that the intercepted money-laundering conversations occurred in 2004, after Arreguin had retired as DEA’s top man in Colombia, DEA sources contend that it is highly unlikely that he was taking part in an agency sanctioned undercover operation. They do concede, however, that it cannot be ruled out that Arreguin might have been part of a covert operation being carried out by a U.S. intelligence agency, such as the CIA, designed to infiltrate or possibly support AUC operations in Colombia.

The latter possibility has to be considered due to the U.S. government’s longstanding support of Colombian President Alvaro Uribe’s battle against the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC — a Marxist-Leninist guerrilla organization. U.S. intelligence agencies have a long history of supporting rightwing paramilitary groups as a wedge against leftist political movements in South America.

In any event, Kent makes clear that DEA agents who reported the alleged corruption outlined in his memo faced retaliation and any subsequent investigations into their charges were whitewashed or otherwise torpedoed. So, it appears the truth of Arreguin’s relationship with the AUC remains a mystery to this day.

Narco News’ attempts to locate Arreguin for comment were not successful. Susie Brugus, Arreguin’s former secretary at the HIDTA office in Indiana, says Arreguin stepped down from his leadership post with the program on Dec. 31, 2007, and has since relocated to Virginia.

Brugus was unable to provide contact information for Arreguin, however. Narco News asked Brugus to let Arreguin know, should they communicate, that we are interested in talking with him, but to date he has not made contact.

DEA officially has continued to discount the allegations in the Kent Memo. DEA spokesman Sanders went as far as to say he “is not aware of any public dissemination of the memo, although I believe it exists.”

It exists all right, and DEA sources say the allegations it contains, if honestly investigated, could prove quite embarrassing to the agency and likely result in the unraveling of a number of current and past prosecutions that are based on information provided by the allegedly corrupt agents. Hence, they contend, there is little chance that the DEA will go that route absent pressure from Congress — which, to date, has shown little stomach for the search for the truth.

But we, as a country, will have to live with the consequences of that choice, which Kent spells out clearly in his memo:

The first four wiretap investigations I worked on when coming to the Wiretap Unit of NDDS [Narcotics and Dangerous Drug Section] all took place in Boston. Working there meant immersing oneself in the turmoil caused by the Whitey Bulger scandal [involving FBI agents corrupted by Boston’s Irish mafia], one which destroyed the credibility of the FBI and to some extent that of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Massachusetts. To my benefit, some of the agents and investigators I worked with were among those who took Bulger’s group and the corrupt FBI agents down. What I learned pales in comparison to what is brewing over at the DEA and OPR [its internal affairs unit]. The failures here are on a scale that dwarfs the Bulger scandal and, as I learned, they are continuing…

Click here for more from Narco News on “The Bogotá Connection”

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.