Clandestinity: Resisting State Repression

Essay #5 from the Book We Are Everywhere

The book We Are Everywhere can be purchased online through the Authentic J-Store at this link. |

By the Notes From Nowhere Collective

November 3, 2004

The Control Society

It’s a Friday night in Seattle. A line stretches down the street and around the block, as hundreds queue to get in to see ¡TchKung!, an infamous eco-punk band. Their shows traditionally end with the performers leading the crowd into the streets, where anything can happen, from occupying an intersection with a “construction crew” handing out drum sticks for people to accompany the band on a giant metal sculpture next to a bonfire, to the crowd racing off to trash an under-construction Niketown. Although they haven’t played in three years, there are many old fans in the crowd entertaining others with tales of outrageous past shows.

But as people enter the club, they come to what appears to be a registration booth for the newly-created Department of Homeland Security (DHS), a Cabinet-level office of the US Government begun in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, which unites previously separate agencies: Federal Emergency Management Agency, the Coast Guard, the Customs Service, and the Border Patrol, and tasks these agencies with the mission of “defending the homeland.”

A large American flag is draped over the table, upon which is a patriotic arrangement of flowers and flags and two laptop computers. Camouflage netting surrounds the whole set-up. Two men in suits staff the table, asking people to volunteer to report any suspicious activities, saying, “It’s up to people like you to keep this country safe and secure.” The laptops feature the website of the Department where one can anonymously submit the name and contact information of any friend, neighbor, or boss who has aroused suspicion. The site also features multiple-choice questions about the “war on terror” so visitors can test their knowledge. Periodically a woman in military garb comes to consult with the men in suits. She wears the DHS logo and seems to be monitoring activities throughout the club. Occasionally one of the men breaks the rhythm of his patter and starts listening to his earpiece. He then pulls someone aside for more intense questioning, maybe asks to look in their bag. Some people are even given “cash” rewards for submitting a name.

A large American flag is draped over the table, upon which is a patriotic arrangement of flowers and flags and two laptop computers. Camouflage netting surrounds the whole set-up. Two men in suits staff the table, asking people to volunteer to report any suspicious activities, saying, “It’s up to people like you to keep this country safe and secure.” The laptops feature the website of the Department where one can anonymously submit the name and contact information of any friend, neighbor, or boss who has aroused suspicion. The site also features multiple-choice questions about the “war on terror” so visitors can test their knowledge. Periodically a woman in military garb comes to consult with the men in suits. She wears the DHS logo and seems to be monitoring activities throughout the club. Occasionally one of the men breaks the rhythm of his patter and starts listening to his earpiece. He then pulls someone aside for more intense questioning, maybe asks to look in their bag. Some people are even given “cash” rewards for submitting a name.

This was, of course, a spoof. However Orwellian the DHS seems, as far as anyone knows it has not yet stooped to the level of recruiting snitches at political punk shows. Yet the response to the spoof was astonishing. At each of the six shows on the Pacific Northwest tour, countless people believed that the registration booth was real. Some people entered the club, saw the booth, and angrily stormed out. Many others attempted to sneak past unnoticed, as though getting away with something. Still others expressed their outrage, shouting angrily about their civil rights being violated, and about government intrusion. Plenty of people gave names (which ended up on the bands’ mailing lists), and not all of them knew it was a joke.

But what was most disturbing was the group that resentfully complied. Refusing eye contact, they shuffled their feet and reluctantly answered questions, looking for all the world like school kids being called before a strict principal and reprimanded. They submitted to the presumed authority, offered their bags up for search, and even begrudgingly gave a few names. No matter how overtly offensive, terrifying, and over the top you get, certain people will still believe you. These particular people submitted out of fear – fear of government, fear that all of their worst nightmares could become reality, fear of the unknown, fear that they were powerless to stop the deluge of repression.

Fear is powerful. It can be all encompassing, completely debilitating, impossible to ignore. Steve Biko, who was imprisoned in South Africa under apartheid, was referring to the power of fear when he said, “The most powerful weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” And it is exactly that fear which the real Department of Homeland Security and its counterparts worldwide rely on to push their agendas further. The more fearful your population, the easier it is to get them to accept oppressive measures, whether it’s censorship, racial and religious profiling, detention of immigrants, or increased powers of surveillance.

Wearing Masks, We Are Visible

Argentina’s unemployed piqueteros blockade roads as a way of putting pressure on local authorities to meet their demands for unemployment benefits. Photo: Andrew Stern |

Clandestinity can be the key to our survival, or it can be our downfall. It can bring us together or deeply divide us. Our clandestinity involves secrecy, marginality, anonymous direct action, breaking the law, hiding, escaping, going underground. It can be a gift to the movement – but it is a dangerous, double-edged gift.

It can render us invisible as secret border-crossers, anonymous web hackers, or workplace saboteurs. It can also neutralize us, if our vast potential support-base only sees us through the lens of spectacularly distorted media as dangerous and frightening. It can render us ineffective if we allow our own fear of repression to create a cult of security that leaves us intolerant, exclusive, suspicious of outsiders and other ways of working, and paranoid. Such groups are among the easiest for the state to break.

We must remember that clandestinity is a tool, one of many that we have available to us. We can learn to use it when appropriate, and set it aside when not. For our clandestinity is easily misunderstood. When we wear masks or disguises, we are accused of being ashamed of the work we are doing; when we work stealthily or at night, we are assumed to be committing dangerous, violent, or illegal actions.

We have studied history, and we know what happens to those who withdraw their consent and fight back – they sometimes are arrested, tortured, driven mad, isolated. As dissenters, our very survival sometimes hinges on our ability to be clandestine, to be secret, to hide, to stay a few steps ahead of our enemy who would reduce us to thoughtless utopians, raving mad lunatics, rabble-rousers, even terrorists. Yet at the same time, we must refuse to disappear, refuse to retreat to the margins of extreme violence and despair. For these are the places they long for us to inhabit, the places where they can set the terms, where they call the shots, and where we slowly become broken and ineffective.

Clandestinity is about protecting ourselves while opening ourselves up to new possibilities, about creating space and sharing it with people we have never met, people with whom we may disagree. It is about remaining ahead of those in power, but recognizable to each other, to those who share our struggles and are looking for us as we look for them. Our proposals and alternatives must also be recognizable, familiar enough to fit the imaginations of all people, and yet shockingly unfamiliar to those in power, as what we want is above and beyond their wildest dreams.

Clandestinity is about protecting ourselves while opening ourselves up to new possibilities, about creating space and sharing it with people we have never met, people with whom we may disagree. It is about remaining ahead of those in power, but recognizable to each other, to those who share our struggles and are looking for us as we look for them. Our proposals and alternatives must also be recognizable, familiar enough to fit the imaginations of all people, and yet shockingly unfamiliar to those in power, as what we want is above and beyond their wildest dreams.

We have a long legacy of clandestinity behind us, protecting us from those in power, who have interminably criminalized us for being different: for being queer, for being poor, for being women, for being people of color, for being revolutionary, for refusing marriage, for being landless, for rejecting the expansion of global capital, for wanting to survive, and for wanting more than merely to survive.

Consistently, we have fought back, sometimes overtly, more often by shape shifting, seeming to be what we are not, going in drag, dressing up, dressing down, disguising our faces, changing our names. Eighteenth-century pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read dressed as men and sailed the seas, terrorizing slave traders and looters of the “New World,” trading the drudgery of plantation life and unfortunate marriages for adventure and freedom.

In England the Luddites, faced with what was the largest repressive campaign ever mounted by the English monarchy, disguised themselves as women, clergy, and military officers and disappeared into the shadows after each night of destroying factory machinery which had made their jobs redundant, often walking through crowds prepared to lynch them, if only they could find them! In the US, Harriet Tubman fearlessly conducted over 300 slaves along the Underground Railroad to freedom – often disguised as a man, and relying on an intricate network of safe houses.

Phoolan Devi, the “Bandit Queen” of India, employed a myriad of disguises after becoming an outlaw at age twenty and spending the next four years living in the desert ravines of northwest India, outwitting the police, leading gangs of bandits in stealing from wealthy higher castes, and distributing the wealth among the poor and lower caste people. In Chiapas, Mexico, an indeterminate number of undercover Zapatistas joined the police force and the military, and then in 1993, volunteered to work on that most difficult shift to fill, New Year’s Eve. The rest is history in the making.

The Enemy Within

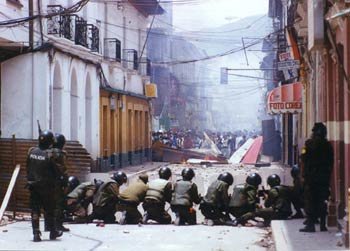

Confrontations between police and the people of Cochabamba, Bolivia over the fate of the city’s water supply resulted in scores of injuries and the death of a young “water warrior.” Eventually, the Bechtel subsidiary which was privatizing the water system was forced to leave the country, and the water remains under public control today. Photo: Tom Kruse |

– Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America – Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent

As the wave of resistance to capitalism swells, threatening to overwhelm it with alternative demands for democracy, justice, and freedom, the powerful are developing and refining a familiar strategy. So we have become witness to hasty retreats, brutal repression, mass obfuscation, and serious attempts to completely discredit the movement. Thirty years ago, intelligence agencies used criminalization strategies similar to those used now in their attempt to thwart vibrant and participatory grassroots movements that had become a serious challenge to the system. Times have not changed much, and we should learn from the history and legacy of our predecessors in order to avoid failure, where many of us end up imprisoned, exiled, dead, or in madhouses.

There is a clearly discernible pattern to criminalization, repeated around the world, and even taught at international policing conferences. The events surrounding the actions in September 2000 against the IMF and World Bank in Prague, Czech Republic described below have direct corollaries in Seattle, London, São Paolo, Cochabamba, Seoul, Melbourne, Cancún, Genoa, Washington – and everywhere people have dared to stand up and say no.

In the months leading up to a mass demonstration the media runs numerous stories in a concerted campaign to terrify local citizens who are not involved in social change and dissuade them from possible participation or support. In Prague, rumors flew between newspapers that international traveling anarchists were descending on the city in order to smash and burn it. Eleven thousand police officers – a quarter of the police in the entire country – patrolled streets during the day, and practiced maneuvers at night. On August 1, 2000, seven weeks before the actions in Prague, the Czech daily paper Hospodarske Noviny quoted President Václav Havel describing the mounting tension in the city, “as if we were preparing for a civil war.” The following day, the Prague Post quoted Prague’s mayor, Jan Kasl, saying that some protesters “will kill if possible, if allowed.”

The tension generated by these declarations reached such a level of intensity that the Ministry of the Interior published recommendations that the population “stockpile food and medicines.” Furthermore, they were instructed to avoid eye contact with demonstrators, refuse their literature, and not engage in conversation with them in order to “avoid suspicious situations that could attract the attention of the police,” and they warned citizens against “watching dramatic developments from a close distance because police will not discriminate when suppressing violence and riots.” The Ministry of Education closed all public schools in Prague for a week, and many families were actually asked to declare in writing that the students would spend that week outside of Prague to “protect” them from the protests. As a result, an estimated one-fifth of the population left town for the week.

In the Prague Post published just prior to the actions, a lead article erroneously linked anarchists to neo-nazi skinheads. Another detailed the increase in business that the summit’s delegates would provide in the city’s thriving sex industry, culminating with a list of “erotic entertainment” clubs – convenient and timely advertising targeted at the international money men. Nowhere was there discussion of the key issues, many of which directly affect the Czech Republic, such as the World Bank-funded Temelín nuclear power plant on the Austrian border. Nowhere was space dedicated to an investigation of exactly who these “murderous” internationals were supposed to be, or quite what they had against Czech plate glass that they would travel from as far away as Colombia, India, Australia, or the United States just to smash windows? The story was written before events had begun to unfold.

In the Prague Post published just prior to the actions, a lead article erroneously linked anarchists to neo-nazi skinheads. Another detailed the increase in business that the summit’s delegates would provide in the city’s thriving sex industry, culminating with a list of “erotic entertainment” clubs – convenient and timely advertising targeted at the international money men. Nowhere was there discussion of the key issues, many of which directly affect the Czech Republic, such as the World Bank-funded Temelín nuclear power plant on the Austrian border. Nowhere was space dedicated to an investigation of exactly who these “murderous” internationals were supposed to be, or quite what they had against Czech plate glass that they would travel from as far away as Colombia, India, Australia, or the United States just to smash windows? The story was written before events had begun to unfold.

This sort of disinformation campaign works on several levels: not only does it undermine any sympathy the local population may have, it sets the stage for the police to move in with the next stage of repression. This generally involves “evidence” linking the protesters to violent activities. It can take the form of a simple press release, such as unsubstantiated news of a group of people turned away from the border because “they had baseball bats and they were clearly not baseball players,” as a spokeswoman for the West Bohemian police force put it. It is unknown if they “were clearly” protesters, as no one has been observed at protests swinging baseball bats, but the association is implied, and the story is repeated and becomes accepted as truth, making it much easier for the police to justify their actions in the days leading up to and during the demonstration. The public has been primed with the message, “Violent protestors will descend on the city causing mayhem and riot,” and of course it is always much easier to frighten people than to get them to take the risk of questioning the status quo.

The next stage of repression takes the form of a police action. The Czech Republic was one of the first European nations in recent times to completely shut down its borders to anyone who seemed like they might be a protester. A Dutch collective coming to Prague to set up a kitchen and provide food was refused entry for 24 hours, simply for wanting to feed people! A train from Italy carrying 800 people from various social movements was held at the border for 17 hours. The police had a list drawn from information provided by Interpol and the FBI – of “known subversives” who were to be denied entry, or possibly deported. Organizers already in Prague were faced with overt surveillance, including being followed and filmed, harassed on the street, and prevented from holding meetings.

Graffiti (“Resistance is Not Terrorism”) in the Occupied Territories viewed through a bullethole while Israeli soldiers patrol. Photo: Tim Russo |

To include more cities in this sort of detailed accounting begins to show a systematized picture of globalized repression. In Washington, Philadelphia, London, and Gothenburg, police raided the convergence centers, confiscated food, medical supplies, and personal belongings, destroyed giant puppets and banners, and in Washington even claimed to have found a laboratory where protesters were manufacturing pepper spray. This turned out to be a kitchen stocked with bags of dried chili peppers and other spices. In another instance in London, they took DNA samples from cigarette butts and soda cans, before having the squatted building – used to prepare for May Day demonstrations – razed to the ground.

In Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, four students were killed and twenty-four wounded during a peaceful sit-in protesting IMF-mandated cuts to public services. In Barcelona, police infiltrated demonstrations, staged fights, broke windows, and violently dispersed a peaceful crowd gathered in a public plaza, after the demonstration had ended. In Argentina, 34 people were killed in a day while rising up in outrage at IMF-imposed financial and banking restrictions. In Québec City during FTAA protests, police staged a night-time raid on the medical center, evacuating healthcare workers and patients at gunpoint into the cold dark night. In Cochabamba, young men who took part in protests to defend publicly owned, affordable drinking water were tortured and one young man was killed.

In Genoa, a letter bomb was sent to a police station in Milan and frequent bomb threats occurred at the convergence center, none of which were thoroughly investigated. This mimicked the “strategy of tension” tactics used in the state-terror campaign against Italian activists in the 1970s. In the climate of fear they created in Genoa, police shot and killed a young man in the streets, and the next night, planted Molotov cocktails in buildings used by the protesters for media, medical, and legal headquarters. The weapons were then used as pretexts for the infamously brutal midnight raid in which nearly a hundred people were beaten in their sleeping bags, 61 were hospitalized, many of whom continued to be beaten in hospital, and 93 were arrested. This list is never-ending; as long as we resist, they repress.

The costs of this repression are heavy. They include the steady elimination of rights and freedoms obtained through centuries of social struggle, the scaring off of people who might otherwise join protests, diversion from serious discussion of the issues, and a drain on our energy and paltry financial resources as we spend months or years at a time fighting excessive legal charges. They also include long-term physical and psychological damage, and the intensification of internal conflicts as we blame ourselves and each other for the repression, which – apart from technological advancements – has actually changed very little over centuries.

This process of state repression – and the media’s collusion through its treatment of our movements as both absurd and threatening – creates a vicious circle which provokes increasingly negative perceptions of activism and struggle, and results in a gradual distancing of the sectors of society that are not directly involved in processes of social change. This enables the state to harden the juridical regime and to redefine as “extremism” or “terrorism” activities whose objectives are to increase grassroots participation in new and truly democratic political processes.

But such displays of force paradoxically reveal the state’s vulnerability. Its mask begins to disintegrate, and we begin to see that what it is protecting so desperately is not natural, not inevitable, but a carefully constructed system which requires massive force and constant effort to maintain. As the Toronto Globe and Mail wryly observed in the week following the Québec FTAA actions in 2001: “The violent response to protesters does not lend credibility to government reassurances that labor, environmental, and democracy concerns about the proposed FTAA will be addressed.”

Engineers of Inequity

The Italian Tute Bianche carry shields and try to force their way through police lines during G8 protests in Genoa. Photo: Meyer/Tendance Floue |

– John Lodge, The Guardian letters page, July 23, 2001

In this time and among a particular few, clandestinity has reached high art. Amidst electronic networks, boardrooms, and the banal spaces of a thousand conference centers, a tiny band of CEOs, politicians, and the “info-tainers” of the media are attempting to construct our collective futures. From their remote locations they declare that history has ended, capitalism reigns supreme, and the expansion of the market is inevitable, natural, and correct. These (mostly) men of money are the noble practitioners of the dark arts of the information age, the wizards of Oz, modern day robber barons waging war on humanity.

They are the three trade ministers who preside in secret over the WTO’s trade disputes panel, whose decisions result in the overturning of national environmental and labor protections, or in punitive sanctions. They are the authors of the FTAA and MAI texts which were only released to the public after months of intense international campaigning. They are the mayor, the police chief, and all major news networks flatly denying the use of hard plastic bullets in Seattle on N30 – while simultaneously the Indymedia website was flooded with photo evidence to the contrary.

They are Riordan Roett of Chase Manhattan Bank, whose infamous leaked memo of January 13, 1995 read: “While Chiapas, in our opinion, does not pose a fundamental threat to Mexican political stability, it is perceived to be so by many in the investment community. The government will need to eliminate the Zapatistas to demonstrate their effective control of the national territory and of security policy.”

They are influential investors such as Marc Helie, a partner in Wall Street’s Gramercy Advisors, who in 2000 refused to agree to a one-month extension on payment of Ecuadorian bonds that he held. Consequently, Ecuador requested a loan from the IMF, who demanded the dollarization of the economy as a loan condition. In January 2000, over a million Ecuadorian indigenous paralyzed the country with protests. And Helie bragged that he was “the man who brought Ecuador to its knees, single handed.”

They are influential investors such as Marc Helie, a partner in Wall Street’s Gramercy Advisors, who in 2000 refused to agree to a one-month extension on payment of Ecuadorian bonds that he held. Consequently, Ecuador requested a loan from the IMF, who demanded the dollarization of the economy as a loan condition. In January 2000, over a million Ecuadorian indigenous paralyzed the country with protests. And Helie bragged that he was “the man who brought Ecuador to its knees, single handed.”

Clandestinity is nothing new to the architects of the global economy. It is the foundation of their entire house of cards, and permeates every structural support.

But their mask is slipping. These wizards behind the curtain are being revealed as lying profiteers playing games with smoke and mirrors, and accounting books. With every corporation forced into bankruptcy, forced into revealing its creative accounting, its complete conflagration of business and government, with every shady deal which comes to light, the mask slips further. Just as with every act of repression – every beating, every murder of a protester, a community leader, a woman or man fighting for a better world – more of their world is revealed, and we deepen our understanding of the true nature of the global economy. It is a nature which institutionalizes poverty, malnutrition, death, and despair, a fact which inspires more and more people to make the leap from believing that there must be something better, to acting on that profound conviction.

As the global justice movement grows, the powerful are forced further into hiding, retreating behind fences – the façades of democracy behind which the decisions are made. These negotiations must remain secretive – after all, they are about the future of continents and the planet, and should not be taken lightly, should not be taken by the people whose lives they will affect.

During protests against the Free Trade Area of the Américas summit of 2001, the entire city of Québec is engulfed in toxic blooms of tear gas, fired at a rate of more than one cannister per minute over a 24-hour period. Photo: Meyer/Tendance Floue |

It has been the goal of most governments since September 11 to contain and disperse dissenters in order to get on with more serious business – that of “fighting terrorism,” war, closing borders, halting immigration, restructuring federal budgets, and restricting civil liberties in ways that make the McCarthy era seem like a minor inconvenience.

Repression has erupted on a worldwide scale, as governments scramble to pass anti-terrorism laws or strengthen existing ones. The USA PATRIOT Act, which sets a new standard of government control, defines domestic terrorism as “acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws” if they “appear to be intended” to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion,” and occur within the US. Because it is written in such vague terms, it can easily be used against peaceful protest, as most protests seek to influence policy, and of course it is the government that determines what constitutes a danger to life. The PATRIOT Act, among other things, also permits indefinite detention of non-citizens based on mere suspicion, expands the government’s ability to conduct secret searches, broadens telephone and internet surveillance by law enforcement agencies, and allows the FBI access to financial, medical, mental health, and educational records without evidence of a crime and without a court order. Similarly over-broad legislation has been enacted all around the world. Countries that have taken radical so-called anti-terrorist measures to crack down on inconvenient internal political dissent include Nepal, Thailand, India, South Korea, the Philippines, Japan, Indonesia, and Britain.

Terms of Engagement

Protesters on the streets of Genoa smash a vehicle abandoned by the conscripted Carabinieri police force during actions against the G8 summit in 2001. The police violence was monumental, with hundreds injured, most notably, nearly 100 activists who were beaten at midnight while in their sleeping bags just one day after one young activist was shot by the Carabinieri. Photo: Meyer/ Tendance Floue |

– Editorial collective of Resist! Fernwood Publishing, 2001

As we become more effective, we will face increasing repression. For it is not our militancy, not shattered windows or graffiti, and not our moral arguments they are afraid of. It is our popularity. It is the growth of the movement, resonating across borders of nation, class, race, gender, age. The truth is: it is when they are most afraid of us that they order their crackdowns.

Until we can recognize this and develop new forms of communication and outreach, we will continue in the endless Mobius strip of debating violence versus nonviolence, diversity of tactics versus clear action guidelines. So instead, what if we collectively demanded that the Black Bloc, who engage in property damage aimed at symbolic institutions of global capital, among other actions, work at developing solid affinity groups and lines of communication amongst themselves and with the rest of us in order to make infiltration of their ranks more difficult? And what if we demanded that the pacifists, who are more likely to practice nonviolent civil disobedience, work at sharing more of their class and race privileges, along with their access to the media, while making a serious effort to have a dialogue with those who wish to engage in different, and seemingly contradictory tactics?

What if we refuse to repeat familiar mistakes such as these: one group claims ownership of an action and all that it contains, freely condemning any who disagree with them; another group proclaims their greater militancy, joining in the moral clamoring by claiming purity, holding their alienation close to heart where it festers and turns bitter, causing everyone to seem like the enemy. What if we agreed that no-one should break windows next to a nonviolent blockade, as it is vulnerable to police attack, and that no-one should physically or verbally assault people engaged in tactics which endanger no-one, and which are appropriately targeted, regardless of whether or not we agree with them?

The very notion of “militancy” is problematic. To pretend that it is more militant to mask up and throw cobblestones at police than it is to maintain a peaceful blockade despite beatings, horse charges, and persistent attacks with pepper spray is deluded. It’s just as deluded as pretending that leading a march of tens of thousands away from a major international trade summit and ending up in a vacant lot is more legitimate than tearing down a much-despised fence which cuts through the center of your city, as happened in Québec City.

Both of these words – militant and legitimate – are infused with a disturbing sense of moral superiority, widening the gap between the groups which claim them as their own. We have seen this trend of romanticized “militancy” before, and we can see how it threatens to shatter today’s movements as it did throughout the seventies in the US and Europe. We have also witnessed the clamoring of certain NGOs for recognition as legitimate dissenters. We should take note of The Economist, which wrote, “The principle reason for the recent boom in NGOs is that Western governments finance them. This is not a matter of charity, but of privatization.”

On the flip side, with the vanguardist application of “militancy,” popular movements in the recent past split into legal groupings and clandestine cells, and from there it was a simple campaign for the state to widen that gap, co-opting the former and infiltrating the latter.

Responding to an escalation of state repression with an escalation of violence, (by which we mean actions which intend to kill or maim people) forces entrance into a profound polarization of tactics, a head on engagement with an enemy more violent, more destructive, and more corrupt than we can comprehend. Using weapons of oppression to fight the state not only legitimizes their tactics, but also makes it difficult to discern any great difference between such groups and the state. In such a scenario, the end does not justify the means, because an end achieved through violence is unlikely to contain freedom or justice. To call for and foment such a dichotomy when there is no mass social base demanding such an escalation not only shows no sense of responsibility to the larger community of people in resistance, but also shows a political naiveté and hubris, as if the world needs another small group of elite urban self-defined “militants” who think that they know what’s best for us and will lead us all into the true path of revolution. It seems that there are enough small groups of elites making decisions for us; we don’t need those which claim to be on our side any more than we need those who turn up on the other sides of the fences in Québec, Bangkok, Genoa, Cancún, São Paolo, or Davos.

However, responding to tactics with which we don’t identify by condemning them and their practitioners, isolating them, in a sense, evicting certain “elements” from the movement and disowning them, forces a collaboration with the state, however unwittingly. If we truly believe in creating a new world which promotes self-determination, autonomy, direct democracy, and diversity, we must extend that belief to our movements, recognizing that there is a place for rage, for impetuousness, for audacity and fearlessness. We must also recognize that nonviolent civil disobedience is not a universally appropriate tactic. Some Brazilian activists complained bitterly that hundreds of activists who attended a nonviolent direct action training led by US activists were then beaten to a pulp during the anti-FTAA actions in São Paolo in 2001. Sitting down in a blockade in front of the Brazilian police force ended in a blood-bath – predictable, say the more experienced locals, who are still trying to rebuild the trust of those who took such a brutal beating on their very first direct action.

Identifying primarily with our tactics (I am a nonviolent activist), or costumes (I’m with the Black Bloc), rather than with our goals, ideas, and dreams makes us rigid and inflexible, completely predictable, unable to evolve. By reducing all of the world’s complex problems to a single target with a single solution, we dally with authoritarianism, vanguardism, elitism. As always, we must find the in-between spaces, the exit from the dichotomy. We must examine each tactic in the context of a specific location and circumstance. As Massimo de Angelis puts it, “The only right tactic is one that emerges out of a communal process of engagement with the other.” And engage we must, as our very survival depends upon it.

Towards the Escape Hatch

Street medics (such as this one in Prague during IMF/World Bank protests) are often the only first aid providers available to people on demonstrations, as ambulances are frequently prohibited from crossing police lines. Photo: Meyer/Tendance Floue |

– Antoni Negri and Michael Hardt

The only way out of the polar terms of engagement laid out by those in power is to recognize that there is no longer anywhere to which we can retreat. There are no safe places in a world which grows critically warmer, a world in which safe drinking water is running out, a world undergoing the greatest mass species extinction since the disappearance of the dinosaurs. We can’t keep going back to the land, starting commun(e)ities off the grid, and insulating ourselves with the safety net of subculture. As Naomi Klein said at the 2002 World Social Forum, “The movement is the escape hatch from the war between good and evil. We know that we have more than two choices.” The only safety is to act now, with great conviction, with a total commitment to increased resistance, with the broadest possible appeal, and a fierce passion for the development of alternatives.

When we succeed at this, it will be impossible to criminalize us. While it is important that people continue working specifically against repression, we must also maintain and strengthen our vision, unleash our imaginations, broaden our constituencies, and develop communication strategies to make plain what we already know: our ideas are in everyone’s minds.

The globalization of repression shows us clearly that our movements around the world have been enormously successful at closing off the spaces into which neoliberalism wishes to expand. It also shows us that no matter how hard they try to beat us, isolate us, imprison us, slander and defame us, infiltrate us, shoot at us, and destroy us, we are winning, we truly are everywhere, and we are not alone.

This essay opens the chapter “Clandestinity” in the book We Are Everywhere. Other stories in this chapter include:

- “Anarchists Can Fly” by Sophia Delaney, US

- “Civil Emergency: Zapatistas hit the road” by Afra Citlalli, Mexico

- “Direct Action: Jail Solidarity” by Notes from Nowhere

- “An April of Death: African students fight World Bank policies” by Committee for Academic Freedom in Africa, Africa

- “Kenyan Students Resist the World Bank” by Jim Wakhungu Nduruchi, Kenya

- “Global Day of Action: A20 - FTAA, No Way” by Notes from Nowhere

- “The Bridge At Midnight Trembles” by Starhawk, Quebec

- “Touching the Violence of the State” by Brian Holmes, Quebec

- “Global Day of Action: J20 - You Are G8, We Are 6 Billion” by Notes from Nowhere

- “Genoa: the new beginnings of an old war, by Ramor Ryan” Italy/Ireland

- “Assassini: the day after” by Uri Gordon, Italy/UK

- “Testimony of Terror, by Morgan Katherine Hager” Italy/US

- “Will a Death in the Family Breathe Life Into the Movement?” by Richard K. Moore, Italy/UK

- “Protecting the Movement and its Unity: a realistic approach” by El Viejo, Italy/Switzerland

- “Direct Action: Action Medical” by Notes from Nowhere

- “International Solidarity: accompanying ambulances in Palestine” by Ewa Jasiewicz, Palestine/UK

For more information about the book We Are Everywhere, see the book’s website. For a special offer to purchase a copy of the book, the Authentic J-Store is now open at Salón Chingón.

Essays from We Are Everywhere on Narco News:

Narco News Publishes Seven Essays from We Are EverywhereEmergence: An Irresistible Global Uprising

Networks: The Ecology of the Movements

Autonomy: Creating Spaces for Freedom

Carnival: Resistance Is the Secret of Joy

Clandestinity: Resisting State Repression

- The Fund for Authentic Journalism

For more Narco News, click here.